Researchers and policymakers in dialogue about the EU Soil Directive and environmental monitoring

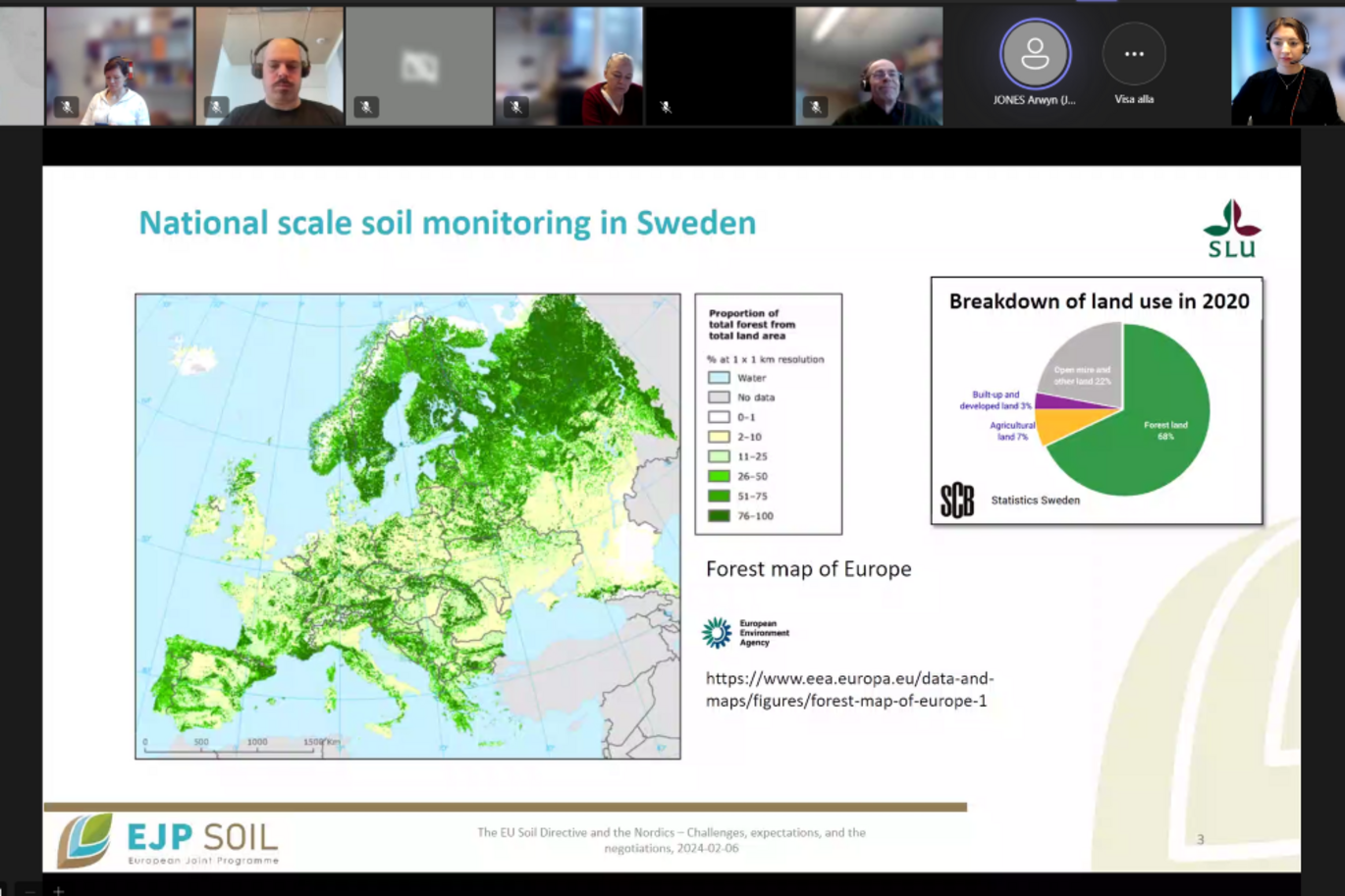

In about 25 years, all soils in the EU should be healthy, according to the European Commission's proposal for a Soil Directive presented in the summer of 2023. The directive will entail changes in our national environmental monitoring programs for soil, but exactly how is still unclear. On February 6, a webinar was arranged where researchers and officials working with the directive exchanged knowledge about existing environmental monitoring programs in Sweden, Finland and at EU level. The current status of the negotiations on the Directive was also highlighted.

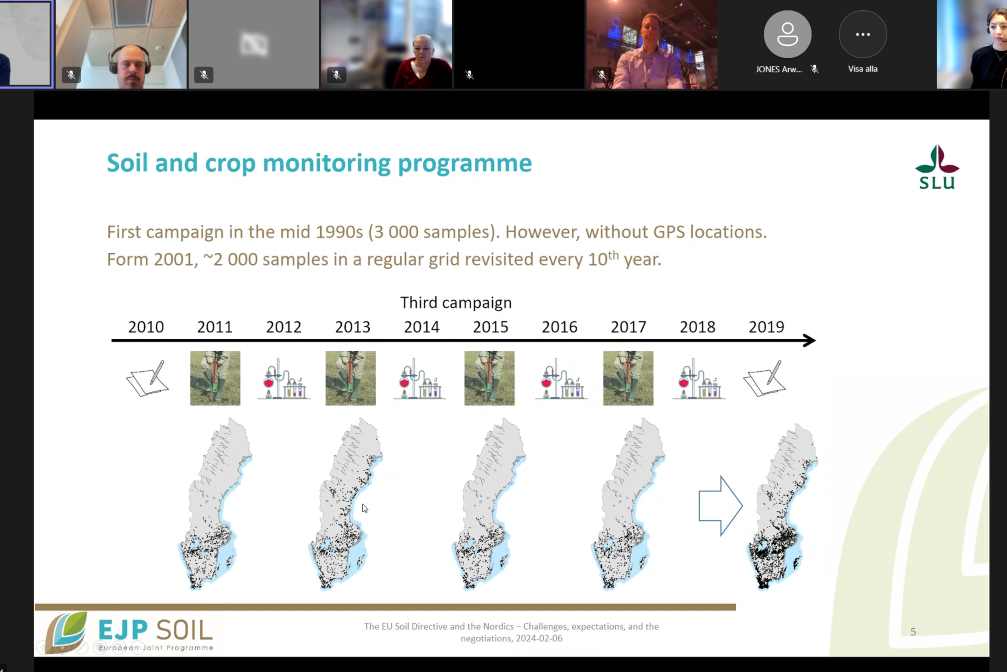

The EU's common environmental monitoring program for soil is known by the acronym LUCAS (Land Use and Land Use Change Survey). Compared to our national monitoring programs in Sweden and Finland, LUCAS has far fewer sampling points and uses another sampling method. In addition, the LUCAS classification of agricultural soils with ley works in a way that categorizes them as grasslands - which makes it difficult to interpret and apply the results in practice. These were some of the differences between LUCAS and the national environmental monitoring programs in Sweden and Finland that were highlighted by researchers Johanna Wetterlind (SLU) and Jaakko Heikkinen (Natural Resources Institute, LUKE) during the webinar.

-The most important issue for us, when it comes to the ambitions of the soil directive to harmonize environmental monitoring in the EU, is that we get the opportunity to maintain our time series that have existed since the 1980s and 90s, said Johanna Wetterlind.

Opportunity to improve existing environmental monitoring

The Soil Directive undoubtedly presents several challenges, such as how to integrate existing monitoring programs with LUCAS and the directive's proposal to monitor more parameters than at present. But there are also opportunities, as pointed out by both Johanna Wetterlind and Arwyn Jones, researcher at the European Commission's JRC.

-The Soil Directive can give us an opportunity to establish LUCAS 2.0, to improve the existing monitoring. For example, soil compaction in the deeper soil layers is likely to be included in the new monitoring, said Arwyn Jones.

The lack of data on soil health in the deeper soil layers was highlighted by several speakers, as was the lack of data on soil biology and physics - such as biodiversity and soil structure.

-We would have liked to collect more data on the deeper soil layers, but this would require more resources than we currently have in environmental monitoring, said Johanna Wetterlind.

Most member states welcome the Directive

The last part of the webinar focused on the EU negotiations of the Soil Directive. Invited speakers with good insight into the negotiations were Paula Perälä, Ministerial Adviser at the Finnish Ministry of the Environment, and Jorid Hammersland, Environmental Counselor at the Swedish EU representation in Brussels.

-Most member states welcome the directive and see that it fills a need, but there are many issues to be resolved before the Council reaches a common negotiating position. One point where opinions differ is on land take, which occurs when, for example, agricultural soil is built on. However, several member states think it is important to keep the national monitoring programs, said Jorid Hammersland.

-We are trying to be constructive in our dialog with other countries and ensure that what the directive says is relevant to our conditions in the Nordic Region. For example, salinization is not a problem in boreal woodlands, and monitoring it does not seem a wise use of limited resources, said Paula Perälä.

Negotiations are currently underway in the Environment Council, where EU environmental ministers are discussing the content of the directive and trying to agree on a common position. The Council will then negotiate with the European Parliament in the fall of 2024. Jorid Hammersland and Paula Perälä believe research can still play a role in shaping the directive.

-We need researchers to tell us what works and what doesn't. What we need right now is constructive feedback on the monitoring framework proposed in the directive, said Paula Perälä.